The following is the introduction to Chapter One by Dr. Jon Moore:

Being a textbook practitioner of the anal arts—please read: compulsively obsessive and obsessively compulsive—I often puzzle over the impossibly complex neural processes that lead a human being even to consider taking her own life. After all, they and their parents, for most people, have already invested at least fifteen years in that life, although for the average suicide—excuse me, suicidal person—this may not have been a particularly pleasant experience.

[Public Service Announcement: This is a long chapter, and completely relevant and necessary, so please bear with me.

Okay, game on again.]

Evolutionarily speaking, when an organism invests that much attention, time and energy into its own life, it is usually unlikely that the organism will destroy all it has worked for, slaved over, plus contributed to a community, helped raised siblings, etc. Yet, despite the strong and well-established evolutionary pressures that favor living, suicide somehow remains a significant killer of our young.

How does one explain this phenomenon to someone who has already begun that long, slow descent into upward mobility—an adult? Let’s try this: have you ever sat down and thought about how long fifteen years really is? If you’re now a middle-aged adult, say, about forty-five, please imagine life at thirty again. Then make your way forward to forty-five, considering the thousands of experiences along the way. Somewhat of a dense blur, wasn’t it? Allow me to sum it up for you: there were probably some career changes, a marriage and divorce, one or two children, death of a parent, significant financial gain (or loss, heaven forbid!), or, perhaps, one or two discreet affairs with a member of any readily available sex.

Rather simple, wasn’t it? Thing is, you handled that big blur with some measure of maturity, either as a grown-up or an adult. Yes, there is a difference between the two: the former is a big kid; the latter, a mature and reasonably adjusted person.

Now go back to age two, which is about the earliest age a normal human can recall anything of note, and repeat the process. Over the ensuing fifteen years, you underwent the most significant changes in your life: fantastic growth of brain and body, from zero to sixty in practically a nanosecond! You also underwent significant development of speech and language, and practiced using all those marvelous senses. And who could ever forget this one? You learned algebra. Through it all you remember the spirit of adolescence and that scourge of puberty, yes? That horrific moment when a fragile young body and brain suffer quantum leaps on countless levels, and time seems to slow to an imperceptible crawl, thus drawing out the pain and agony to impossible limits.

To cap it, Mother Evolution doesn’t even provide a modest owner’s manual for a young child, not that she would read it. Even though all parents experienced puberty in one form or another—and raced to forget the whole process—they’re still at a loss with how to cope with it, with their own child. They, too, would just as soon forget that horror story.

Point is, the early years of a child are so unbelievably packed with highly compressed information that simply disallows the child any real comprehension of her own being at that time. It’s as if the human body attempts to speed through the necessitous process of incredible growth, begging the child to close her eyes and just go along blithely for the ride.

My goodness. I encourage you to re-read the above paragraph, as it truly explains in general terms what a child goes through in her first fifteen years of life.

When I first began treating suicidal patients, I would often remind teenagers how young and malleable they truly were, and that they’re really just starting their lives and will soon outgrow the pain. Hold on just a little longer, I would plead. It became a mantra that I hoped every child I saw would repeat to herself every time pain surfaced, and then share the lesson with others.

On more than one occasion, one of them retorted, “Fifteen [Expletive deleted.] years was a long [Expletive deleted.] time to be [Expletive deleted; yes, again.] unhappy.”

Even though we studied this phenomenon in medical school and during my residency and fellowship, it didn’t hit home until I was practicing on my own.

Therefore, when I saw it in those terms described by more than one young patient, I took a different view of what kids go through when contemplating suicide. I also learned that a year to an adult or reasonable grownup is 365 days. To a child, especially a suicide, a year is “hellacious infinity,” everywhere, every day. Period. And whatever pain inhabited a child at that time, it felt like it was in permanent residence.

What a frightening reality, the thought of living 24/7 in a completely helpless state, one that never dissipates, let alone disappears altogether.

That’s what a child in pain feels and is encouraged to live with, struggle through, and come out the other end as a well-functioning adult.

For kids, time is compressed, much like a Slinky at rest. When life is going relatively well for a child, time marches on very quickly and the Slinky remains compressed and appears relatively short, although physically it still contains the same amount of “time” or experiences to us adults. The alternative is to consider that the Slinky really is several times longer stretched out, which corresponds to real time to an adult.

When things turn for the worse, a child’s time-spring painfully decompresses, or elongates, into what feels like an interminable forever. What was previously short and sweet is now hours or weeks. That Slinky went from being a short spring to an impossibly long coiled wire that seemed to spin and kink out of control.

A year to a child, as I said, is an impossible infinity. Children in pain can’t even fathom the concept of a week. It’s only relative as it relates to a school week, a vacation or the coveted weekend.

What’s often worse, too, is that a child’s timeline can become syncopated, where small and large events are dropped from conscious memory. There’s too much sensory input for children nowadays, and social evolution pressures them to inhale and store as much as possible during every gulp of life.

While adults tend to feel that much of what kids absorb is garbage, the kids themselves sense things differently. To kids, “garbage” is exciting and entertaining, and forms a great part of their foundation as they grow into adults. One adult’s garbage is another child’s useful and necessary fantasy. We can also look at how children play in the dirt, which adults see as, well, dirt. That so-called dirt contains all manner of bacteria, fungi and other creepy invisibles that contribute greatly to a child’s healthy immune system.

I’d like to add one additional analogy that may help describe the vast differences between adult reality and kid reality, using my favorite subject: physics. Adults can be thought of in terms of large molecules, whose gross molecular behavior can be approximated using classical Newtonian mechanics, something we all learn in high school physics.

If you were one of those who, ah, shunned the sciences, then please skip the next several paragraphs.

Newtonian mechanics can describe gross behaviors, like the movement of individual atoms and molecules from one place to another via a process known as diffusion. Or the ionic or covalent bonding of one atom with another.

But classical mechanics seems to break down below the atomic level, where funky forces come into play.

How does this apply to a child? The behavior of children can adequately be described—analogously, of course—not by classical mechanics but by quantum mechanics, which govern the behaviors of subatomic particles, well below that of “adult” molecules.

At the subatomic level, all sorts of funny physics goes on: particles move in strange and unexplained ways, new and fascinating forces create actions never before seen at the much-larger molecular level. Only someone who understands the nuances of quantum physics can fully appreciate the myriad effects at that level. A traditional physicist who only studied classical mechanics and electrodynamics may have considerable difficulty understanding the behavior of particles at the subatomic level, or may not grasp anything at all.

Imagine that: an adult who cannot communicate with or understand a child on any level. Maddeningly frustrating, isn’t it? Some parents pull their hair out.

Adults are like large molecules; children are like subatomic particles like electrons, protons, neutrons, quarks, gluons, etc. As one can imagine, the strange goings-on within an atom—analogously, a child’s mind—are not governed by any “adult” laws. Therefore, kids should be seen as separate and distinct entities, and should never be viewed as “miniature adults,” regardless of how mature a child may appear. The physical laws and rules that govern the life of each precious child are a complete mystery to most adults.

Armed with information like this may allow a child psychiatrist to view and work with kids on a level far different and often more fascinating than that of adults. In effect, a good child psychiatrist delves well beyond condensed-matter physics; he becomes a practitioner of the voodoo arts that appear to define quantum mechanics. Of late, I was neither. And this was beginning to concern my staff, not to mention what was left of my delicate psyche.

Pain often forces a child to ignore certain events and stimuli, which can make treatment very difficult. How do you ask a child to explain how or why they feel mentally dysfunctional? How do you expect a child to even begin to answer a question like that?

We adults are obligated on many levels to fully understand how a child sees reality, and learn to separate theirs from ours. We tend to want our children to face reality as if these kids actually understood adult reality. They don’t. And, unfortunately, most parents don’t understand the reality of their own kids, even though parents went through it themselves. Society has trained children to act as society expects, not as these children would act if their creative freedom and dignity were intact and continually nurtured.

Sometimes, I wonder if some parents were hatched from alien eggs. They often ask kids the most irrelevant questions. A good example: “Do you understand me?” The traditional answer kids give is a nod of the head or a simple yes. Do you honestly think those kids are telling us the truth? When was the last time you heard a parent ask the child to explain what the parent just said, but in the child’s own words?

The second-stupidest question in the English language that adults and grownups ask children really kills me: “Why did you do that?” My goodness! Here’s what parents need to know: children are great sponges of vast amounts of information, and they have very little, if any, time to analyze those incoming data, let alone how to respond to them in a way we can understand and act on.

Parents and people in general do not realize that our conscious self—a simple bus driver who gets us from Point A to Point B—is the one being interrogated and it has little access to the valuable information others seek from us.

That information is stored and processed in one’s subconscious, the deep entity that communicates information from The Universe to our conscious self through dreams and dreaming and the occasional daydream or little mental itch you sometimes feel. Your subconscious talks to your bus driver by that “nagging little voice” in the background that reminds us not to do or say anything stupid. Unless we listen to those communications, we are sometimes at a loss to explain ourselves coherently. Things get worse when we are stressed.

And please don’t tell me it was Freud who invented all this cool information. He was a manufactured fraud who was directed to “present” his so-called ideas to the world. Pure propaganda, so please do not believe his poop. You can believe mine, though, because it’s accurate.

Anyway, where were we?

Oh, yes!

So how could we possibly expect a child to answer us accurately?

It’s nearly impossible.

A child storing all that information is already like drinking water from a fire hose. Blasting on high. We adults and grownups should not ask children to evaluate, much less be responsible for, inbound information. The process of human physical growth has been honed by evolutionary pressures for millions of years, so we’re obligated to let Mother Evolution take her course in the development of our children, with nurturing supervision.

Yes, children do learn to associate their parents’ words and emotions with relevant actions and behaviors. But parents often expect too much too soon because parents don’t understand it themselves.

What people fail to appreciate is that children must go through certain steps during early years, and must be allowed to act and behave like children. When those steps are removed or shortened to make room for more adult behaviors, the child loses an important part of their emotional growth, thus rendering them basket cases as adults.

There’re countless cases of child prodigies who failed miserably as teens and adults because parents and society pushed too hard. Some stories ended well. Others, at the morgue.

What brings on thoughts and feelings of suicide? I can hear you now: “Information overload, you idiot. Get on with the story!”

Often, it’s merely a chemical insult that begins with some form of trauma, be it physical or behavioral or externally chemical. Other times, I’ve ascribed demonic intrusion as the root cause. I know it sounds silly, but demons do exist. I’ve seen them in parts of West Africa, where I studied briefly, and even a few in south Florida. While I don’t think Tripsy is possessed in any way by a demon from a netherworld, I wished to include it as a prospective cause of suicidal thoughts, in general.

Over the years, I’ve often found it helpful to ask this simple question of my patients contemplating or threatening suicide—why do you want to kill yourself?—and then just encourage them to talk for the entire session. Often enough, they discover for themselves that suicide would not be in their best interest. And we both often find that they just needed someone to listen to their thoughts and beliefs, ideas and dreams, wants and wishes.

Recently, though—perhaps out of pure laziness—I’ve found it easier just to medicate patients and free them of the burden of abject pain, especially kids who may never have the mental faculties to understand their own self and behaviors.

It’s true that some patients can be successfully treated using behavioral therapy, but many have to be medicated, sometimes for many years, if not a lifetime. Sadly, the cause is often some insult by family or society, including the poor quality of food, water, air and other chemicals. Behavioral trauma also adds to the mix in countless ways.

Of course, there’s always the odd patient who believes that nothing short of killing themselves, and perhaps taking me with them, is the only recourse. At those times, I feel the need to be fully armed with a medium-size box of 10-mL syringes, each filled with 40 milligrams of diazepam. In case you’re not sure what diazepam is, look up valium in the dictionary. Forty milligrams is enough to put a small horse into low-earth orbit for a week. Although I’ve yet to deploy it in combat against a child, I imagine an appropriate dose would cause immediate drowsiness and then put her into a deep, comfortable sleep. Hopefully, not too deep.

I have often thought of keeping on hand a small handgun for the truly odd patient whose chemistry resides to the far left of The Great Bell Curve, but I’ve found that merely brandishing a box of syringes with long hypodermic needles is more than enough to shock the patient back onto the couch and into her own head, however dangerously radioactive it may be at that time.

Did I also mention my 130-dB atavistic scream that follows the brandishing of the syringes?

One of my assistants, who happened to be present during one particular patient’s rampage, quietly assured me that it was the scream that arrested that patient and welded her Converse All-Stars firmly to the floor.

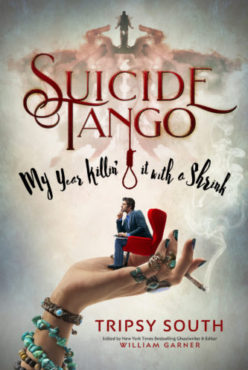

Tripsy was quite—how to put it?—passionate about verbally expressing her beliefs, without being physically violent. Janice, my chief of staff, once referred to Tripsy as a “booming loudspeaker operating at full volume in an empty stadium and filling it with nothing but Tripsy.”

I also recall her relating to me, “Tripsy didn’t even have to be plugged in. She operated on her own power, and there seemed to be an endless supply of it, thus probably violating several important universal laws of physics. She’s a true force of nature, probably not of this earth. With that said, Jon, you’re probably in a lot of trouble.”

I respectfully concur. In fact, I was fast developing a hypothesis that Tripsy was an Indigo Child. I’ve studied this archetype over the years: very rare in number, personality, neurochemistry, behaviors. I’ve only come across one and he was someone else’s patient who was referred to me for a second opinion. I was so in awe of him that I wanted to drop everything I was doing so I could study him for the rest of my life.

Sadly, though, he took his own life at just thirteen years old, shortly after he returned to his native Scotland, in Edinburgh. Didn’t leave behind a letter or any indication that he was suicidal.

Liam knew that he couldn’t possibly live in this world of such volatile intemperance and ignorance. Withdrawing into himself was his last refuge in the final months of his life, and that wasn’t enough for him. I was heartbroken when I heard the news, yet I understood this boy’s motive completely. I don’t think he was suicidal at all, and I wanted to tell the world but I knew no one would listen let alone understand.

So much of his unusual chemistry was now right on front of me, and I wondered how I should approach this case. Would Tripsy slowly slip away from all of us like young Liam did?”